“You cannot dress yourself too beautifully for your friend, Friedrich Nietzsche said. “For you shall be to him an arrow and a longing for the overman."

Let us, for now, leave aside the question raised of the overman, or Übermensch. Look at the first part of the sentence. Does Nietzsche mean it is impossible to be too beautiful for one’s friend, because one’s friend always deserves to behold the very highest beauty? Or does he mean, the opposite? To be careful not to dress oneself excessively beautifully for one’s friend?

Two photographs of myself—

The first is a photograph of myself without the SNOW app beauty-enhancing filters applied (although the color saturation, contrast, etc., is enhanced), the second is one which has the filters applied. I am (or appear to be) more real, more truly myself in the first photograph. Yet my instinct tells me I am more beautiful in the second.

The poet and author Anne Carson wrote, in her text The Beauty of the Husband,

“Not ashamed to say I loved him for his beauty.

As I would again if he came near.

Beauty convinces.

You know beauty makes sex possible.

Beauty makes sex sex.”

Rainer Maria Rilke, in his Duino Elegies—

For beauty is nothing /

but the beginning of terror /

which we are barely just able to endure /

and we are so awed by it /

because it serenely disdains /

to annihilate us. /

Every angel is terrible.

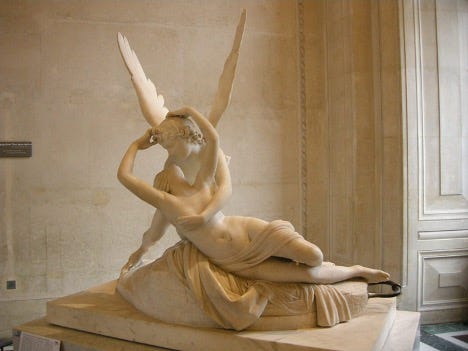

The desire to be beautiful or to possess beauty is perhaps universal. Fables abound in literature and history of beautiful people, especially beautiful women, having a quality or degree of beauty which crosses a threshold into such an extreme as to induce conflicts, and inspire men to fight great wars. Virtue and beauty are not identical, but there is a tradition of “beauty” reaching mythological proportions which may be argued to be a proto-ethics and perhaps a neo-ethics as well. Nietzsche says that men love to use women in their imagination as symbols; before image of the beautiful woman in one’s mind, men imagine they are “carrying a goddess over a flowing stream”—even if this is possible only at the price of separation from the woman herself—if only they apprehend a beautiful woman as truly beautiful at a distance. “Beauty convinces,” as Carson says, because of what Rilke explains, that “beauty is nothing / but the beginning of terror.” When we behold the beautiful, especially the Kantian sublime—definitionally Rilkean in that it is dangerous—we feel ourselves in the face of something whose sheer physical existence is so moving that it might induce us to violate, or wish to violate, the laws of ethics, of jurisprudence—even physics.

This is probably why so many traditional, conventional systems of morality caution against the possible deleterious effects of the company of a beautiful woman. Conventional morality teaches us that a beautiful exterior indicates a lack in a woman’s interior world. Blonde jokes tell us blondes are stupid, popular interpretation implies, in a way that is somehow causally related to their beauty. Blondes, apparently, are stupid because people find them beautiful—even if in reality, neuroscientists can use brain imaging to teach us that motherhood erodes grey matter in the brain, and therefore a lack of brain cells could just as easily be the effect of a woman becoming a mother as anything else. It is not clear to me that to be a mother is a form of stupidity!

The beautiful is not identical to the stupid—the ugly can also be stupid, and the beautiful can sometimes be the most brilliant among us. Yet the risk of a beautiful stranger inducing someone to betray themselves, their family, friends, community, or their values and principles—that is what Anne Carson means by “beauty convinces,” and what Rilke meant by saying it is nothing but “the beginning of terror.” It is a traditional value and has a powerful truth, at least at its seed. For all of us want to be beautiful.

Personally, I would never sincerely think of myself as ugly, even if I would be happy to be more beautiful than I am. Once a great love took hold of my life, and the effects of that lover, that friendship, will be with me now until my life extinguishes. That lover of mine taught me I was innately and deeply beautiful, and that certainty is something no one can take away from me. He established in an argument with his father that Hannah Arendt was in fact a beautiful woman, contradicting the norms which prevail claiming that to be beautiful necessarily entails stupidity—which also implies the converse, that an intelligent woman is necessarily undesirable. Is anything undesirable about Hannah Arendt?

This phenomenological dialectic, between the desire to be more beautiful with the certainty that one already is beautiful in abundance, is no frivolous topic. Rather it constitutes a part of an inner conversation which is very important to my own spiritual, religious and philosophical development: in striving throughout my life both to flourish in the sense of eudaimonia, but also to be as good in the sense of virtue as I can.

I am afraid of how technology affects our desire to be more and more beautiful.

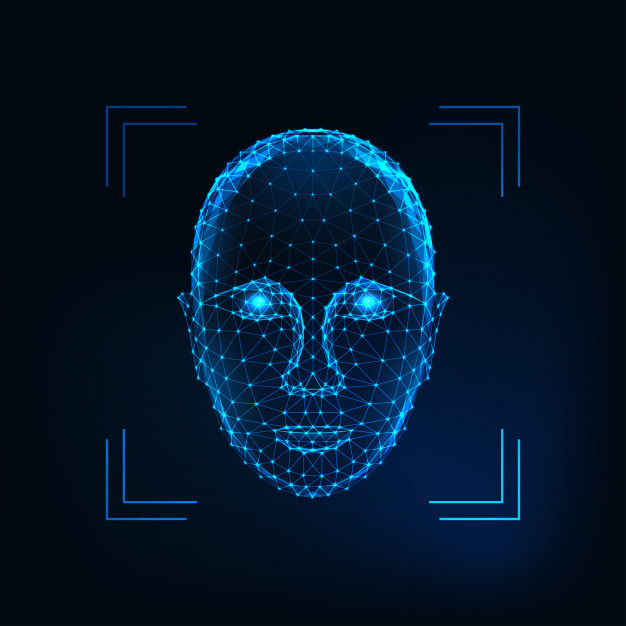

What are the ethics of incentivizing people to become more and more enmeshed in the “matrix” of these databases? Especially in a post-pandemic world where more of us are isolated, and more of us have shifted at least some of our social interactions which used to occur face-to-face into the virtual world. What does it do to me if facial “beauty enhancement” apps such as SNOW, which can simulate changes to your very bone structure, have the ability to potentially induce me to believe I should not look as I do on a deeper-than-surface level—to the bone? Or to induce me to believe—worst of all—that I am not beautiful? This is not a trivial question—beauty is a tool, after all, or even a weapon—and it is very often more useful and valuable to be beautiful than to not be.

Yet there is a profit incentive to do so—and if face-altering (“enhancing”) apps convince me that I am insufficiently beautiful without their effects, it is not necessarily just for the sake of profit, but can be for state interests as well—facial recognition technology and other types of biometric data are critical, emergent, but also potentially volatile and dangerous tools now available to law enforcement thanks to companies like Clearview AI. So many questions arise. If there are state interests, so much depends on which state.

On the one hand, I appear more real in photographs without beauty-enhancing apps, more true to life, although a photograph will still never be same as my real self. Is that better? Perhaps it’s not valuable to appear real in photographs, except in certain instances.

On the other hand, I appear more beautiful in photographs with the use of beauty-enhancing apps. But what does this do? Appearances can deceive people who meet one another online that the other (sometimes the beloved’s) appearance is otherwise than it is, leading to deflated expecations of romance. Another serious concern: it can also be a vulnerability if entry into some specific facial recognition database, in the hands of a bad actor, makes me vulnerable to some form of, say, political persecution. It is not good if I was led there by a feeling that I am not beautiful enough as I am. Third, artificial or technologically ubiquitous simulations of beauty can tranquilize us and distract us from the fact that we are spending all of our time alone, as consumers of social media and videoconferencing platforming, without the types of real in person community that makes us human beings!

Let us step away from the political and speak of the private sphere. Let us speak from the first-person phenomenological perspective. I think each human being has both a desire and a potential to be beautiful. I believe what we can take away from these phobias about the power of facial recognition databases is, firstly, this: we must invent and cultivate practices in our lives, and in our etiquette (which can eventually become our ethics) which can inure human beings to those delusional paths which teach us we are not beautiful.

As for me, I do not need it. I possess absolute certainty that I am beautiful. I owe that certainty to the great love I mentioned previously, and even if I cry because he has not spoken to me in ten years, to kiss my tear-soaked face would still taste sweet. For as a friend he has given me a gift no one can take away from me. I am beautiful! Thanks to him, there is no one who can dissuade me of that.

It may be a long while before the highway

Decides to finally set me free

I'm going to have to chase down the remnants

Of something special that you stole from me

It may be hiding in the sunset or in distant corners of the dawn

Or maybe it's gone

But I say some prayers above the engine

I bless everything there is to bless

Run out of gas in the middle of nowhere anyway

Stand by the roadside smiling

And take a picture of my dress

I take a picture of my dress

—John Darnielle of The Mountain Goats; from the song A Picture Of My Dress